The Bilharzia Prevention Communication Campaign was implemented by the Uganda Ministry of Health Vector Control Division, with technical assistance from The Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, and funding from an American philanthropist.

The campaign ran from August 2017 through May 2018 and reached a large proportion of Ugandans living in endemic areas of the country. It raised awareness about the disease along with how to prevent it, and encouraged many to adopt preventive practices.

The campaign tools, materials and the process followed are presented here to guide similar efforts in Uganda and elsewhere.

Banner photo: Students respond to a question from the outreach working teaching them about Bilharzia, Kabarole School, Uganda. Credit: Nikki Lettenmaier-Scott

Background

What is Bilharzia?

Bilharzia, also known as Schistosomiasis, is a parasitic infection spread through contact with contaminated fresh water. The parasite enters through the skin and takes up residence alongside blood vessels where it produces eggs that are excreted through urine or feces. Over time, the eggs also clog blood

Bilharzia, also known as Schistosomiasis, is a parasitic infection spread through contact with contaminated fresh water. The parasite enters through the skin and takes up residence alongside blood vessels where it produces eggs that are excreted through urine or feces. Over time, the eggs also clog blood vessels and can cause tumors in the liver, spleen, kidneys and other organs, leading to irreversible damage if not treated. When an infected person defecates or urinates in or near a body of water the eggs enter snails residing there and hatch into the parasitic form that infects people.

The best way to prevent infection is to avoid direct contact with water contaminated with Bilharzia. People can reduce their risk of Bilharzia infection by defecating and urinating in toilets or latrines, and never in or near a fresh water body.

Inquire

CCP engaged a consultant to conduct a desk review on Bilharzia in Uganda, with a particular focus on relevant knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices associated with its prevention and control.

At the same time, Performance Monitoring and Accountability 2020 (PMA2020) Uganda was analyzing findings from the 2016 Schistosomiasis Survey. These activities took place between January and March, 2017.

Prevalence in Uganda

According to a nationally representative survey conducted by PMA2020 in 2017, 29% of people two years of age and older in Uganda are infected with Bilharzia. Infection is highest in children two to four years of age at 41.9%. Among adults, only 4.1% reported ever having Bilharzia, indicating that the vast majority of Bilharzia-infected Ugandans are not aware that they are infected.

children two to four years of age at 41.9%. Among adults, only 4.1% reported ever having Bilharzia, indicating that the vast majority of Bilharzia-infected Ugandans are not aware that they are infected.

In 2016, only 56% of people over five years of age in Uganda had heard of Bilharzia, according to the PMA2020 baseline Schistosomiasis survey. This increased to 69.9% in 2017, after the Bilharzia Prevention Campaign had been underway for only 3 months.

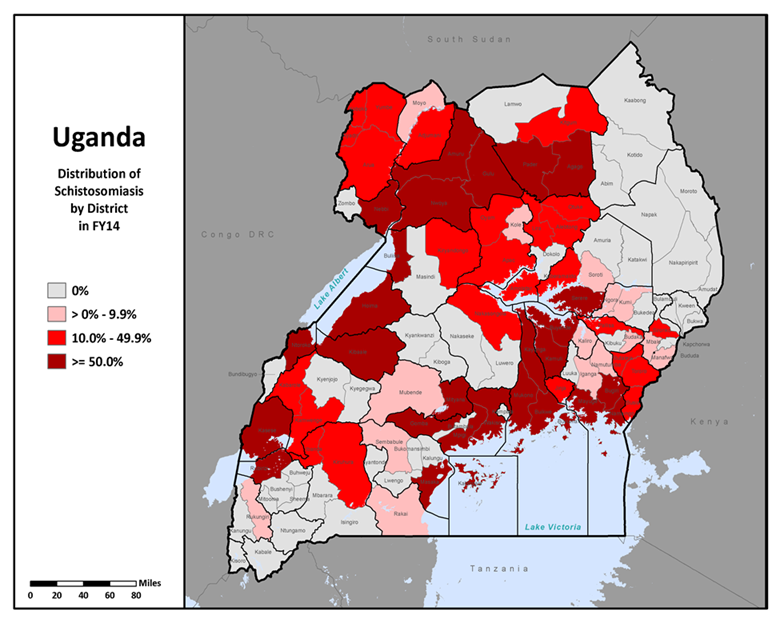

Since 2003, the Uganda Ministry of Health has been implementing a National Bilharzia Control Program aimed at controlling the disease through mass treatment with Praziquantel in endemic areas of the country. Districts are categorized as highly endemic (prevalence ≥50%), moderately endemic (prevalence of 10% to <50%) or non-endemic (≤10%). Mass treatment is administered to all people five years and older every year in highly endemic districts; and every two years in moderately endemic districts.

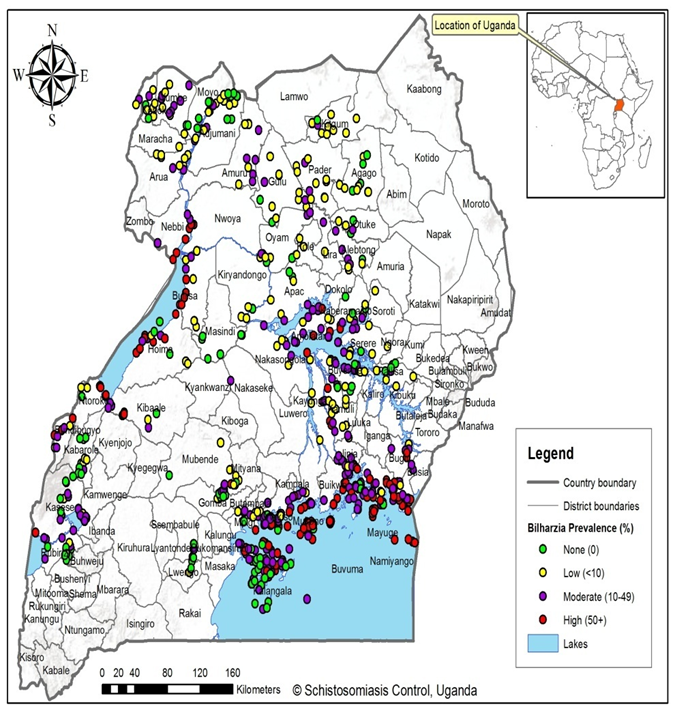

The map above shows distribution of Bilharzia in 2014. The map below shows Bilharzia prevalence in Uganda in 2016.

- Schistosomiasis (“Bilharzia”) Monitoring in Uganda, Round 1 October–December 2016

- Schistosomiasis Situation in Uganda: A Review of Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP) associated with Schistosomiasis Infection and Prevention

Design the Strategy

In March 2017, CCP assisted the Vector Control Division in conducting a two-day campaign design meeting with stakeholders involved in Bilharzia control in Uganda. During the meeting, stakeholders shared and considered findings from the desk review; lessons from implementing the Bilharzia Control Program; preliminary findings from the Performance Monitoring and Accountability 2020 (PMA2020) Schistosomiasis Survey; and experiences of Vector Control Officers working in endemic districts.

Reflecting upon learnings from these sources, stakeholders crafted a strategy that addressed the causes of high Bilharzia prevalence and associated morbidity, namely:

Reflecting upon learnings from these sources, stakeholders crafted a strategy that addressed the causes of high Bilharzia prevalence and associated morbidity, namely: frequent contact with contaminated water; open defecation and urination, especially in or near water bodies; and less than 100% uptake of Praziquantel.

The Bilharzia Prevention Communication Campaign strategy is based on the Extended Parallel Process Model (EPPM). According to this model developed by Dr. Kim Witte, the degree to which a person feels threatened by a health issue determines her motivation to act, while one’s confidence to effectively reduce or prevent the threat determines what action she will take.

The media campaign plan focused on two primary audiences in Bilharzia endemic districts of Uganda:

- Adults who are at high risk of Bilharzia. These include parents of children who are also at risk. These adults and children have frequent contact with lakes, wetlands or rivers.

- School-aged children (five –twelve years old) living near lakes, wetlands or rivers.

The campaign aimed at raising awareness about the disease, building a sense of vulnerability, and encouraging three practices to reduce one’s risk of Bilharzia:

- Avoid direct contact with lake, river, or wetland water;

- Take the Bilharzia medicine distributed free of charge in schools and communities; and

- Use latrines or toilets, and never defecate or urinate in or near a water body.

To reach the largest number of audience members, the campaign used radio as its main communication channel, supplemented by a job aid for community resource persons, teachers, and health workers.

- A Media Campaign to Prevent Bilharzia in Uganda

- Schistosomiasis Prevention Communication Campaign Plan

Create and Test

Creation:

Between April and mid-August, CCP designed campaign materials and activities. The campaign strategy called for the following activities and materials:

- Radio jingle/theme song

- Flipchart job aid

- Radio spots

- Radio skits

- Series of six expert hosted radio talk shows (60 seconds each)

- Outreach community radio programs

For each of these activities, CCP prepared creative briefs that describe how each would look, their audiences and objectives, and message content. CCP engaged the services of an advertising agency to design and broadcast radio materials and to develop the job aid, based on the creative briefs.

Radio materials were initially produced in 12 languages plus English; after December, when the campaign was extended to additional districts, they were produced in six additional languages. CCP worked closely with the advertising agency and Ministry of Health representatives to select radio stations and Bilharzia experts for the call-in talk shows, and prepared guides for radio talk shows and community outreach radio programs.

The key messages to be communicated were:

- How Bilharzia is spread and its dangers;

- Bilharzia is not caused by witchcraft; it can be prevented and treated;

- How to reduce the risk to Bilharzia for yourself and your children;

- If you/your child have to be in the water for any reason, do it before eight am when there are not so many worms in the water

- Bathe yourself/your children with water from a protected water source if you have one. Avoid bathing yourself/your children in the rivers or lakes.

- If you must bathe in lake or river water, collect water for bathing and keep it for 24 hours before you/your children use it. Do not bathe in lakes or rivers.

- If you/your children have to wade in the water, wear boots

- If you/your children have to do anything in the lake or rivers, limit the amount of time they spend in the water

- During Mass Drug Administration (MDA), take your PZQ as instructed and ensure that your children take it as well

- PZQ is not a vaccine against Bilharzia but a treatment for Bilharzia. You have to continue protecting yourself and your children to avoid getting Bilharzia again.

- PZQ can have side effects. Take food before PZQ to reduce the extent of the side effects.

- If you or your child have frequent bloody diarrhea and feel abdominal pain, it could be Bilharzia. Visit the nearest health facility.

- If everybody uses a latrine, the bilharzia transmission cycle will be terminated. Always use a latrine. Do not defecate or urinate outside a latrine. And, never defecate in rivers, lakes or wetlands.

Pretesting: To ensure that campaign audiences could easily understand and relate to the materials, CCP organized focus group discussions with audience members and shared draft materials with them. Following a discussion guide, moderators asked audience members for their reactions to the materials, and how they could be improved. CCP pretested materials in all languages, and revised them according to audience inputs.

Expert review: CCP also shared the campaign jingle and scripts for radio spots and skits with Bilharzia experts at the Vector Control Division to ensure accuracy and consistency with Ministry of Health policies and strategies. Before finalization, CCP shared materials in all languages for final review and approval by the Ministry of Health.

- Creative Brief for Radio Skits for Uganda Schistosomiasis Prevention Campaign

- Bilharzia Campaign Radio Show Guide

- Concept Paper for Community Radio Talk Show, Bilharzia Campaign, Uganda

- Community Outreach Broadcast Guide for Bilharzia Campaign, Uganda

- Bilharzia Campaign, Uganda – Radio Spots

- Bilharzia Campaign, Uganda – Radio Skits

- Bilharzia Campaign, Uganda – Pretesting Methodology

- What Everyone Should Know about Bilharzia: An Aid for Community Sensitisation

- Radio Jingles for Bilharzia Communication Campaign, Uganda

Mobilize and Monitor

Mobilization and monitoring of the campaign involved the following:

Preparing a broadcast schedule:

The advertising agency negotiated broadcast schedules with the radio stations selected for the campaign. CCP decided to broadcast on community radio stations rather than large national stations for two reasons: 1) to reduce costs; and 2) to target broadcasts to endemic areas of the country, using local languages. Selecting the days and times for broadcasting radio call-in talk shows needed careful coordination with local Bilharzia experts (mostly Vector Control Officers based in the districts) who were fluent in the local languages.

Orienting radio presenters and Bilharzia experts:

Before any call-in radio program’s broadcast, CCP and the Vector Control Division conducted one-day orientations for the Bilharzia experts and radio presenters assigned to each program. Presenters and Experts were oriented to Bilharzia, the campaign strategy and materials, and the guide for the radio programs, which included content outlines for each program.

Organizing community outreach radio programs:

After the call-in programs began broadcasting, CCP and the advertising agency turned their energy to designing community outreach radio programs. CCP prepared guides for outreach radio programs, and coordinated among radio stations and Bilharzia experts to select locations that could be reached easily by

After the call-in programs began broadcasting, CCP and the advertising agency turned their energy to designing community outreach radio programs. CCP prepared guides for outreach radio programs, and coordinated among radio stations and Bilharzia experts to select locations that could be reached easily by both and, to the extent possible, where mass distribution of Praziquantel was scheduled to take place. Before the outreach programs took place, CCP and the Vector Control Division oriented the radio presenters and experts to the activity guide. During all outreach programs, CCP deployed consultants to supervise, monitor, document and troubleshoot the activity.

Establishing a campaign monitoring system:

CCP put in place a system to monitor whether or not broadcasts took place as scheduled; the quality and accuracy of radio call-in programs; the quality and accuracy of community outreach radio programs; and feedback from radio program listeners and community outreach participants.

CCP contracted a commercial media monitoring company to monitor broadcast schedules. This company provided monthly reports to the advertising agency and CCP, indicating the number of broadcasts missed, and the number of unscheduled broadcasts. The advertising agency used this information to demand re-broadcasts for those that were missed.

CCP employed two full-time consultants to monitor and supervise the quality, content, and audience feedback during call-in and outreach radio programs. One was assigned 12 and the other, 13 radio stations. These monitors ensured that Bilharzia experts appeared on programs as scheduled, assured that presenters and experts adhered to the program guidelines, identified any incorrect information and made sure it was corrected in subsequent programs, recorded the number and content of radio listeners’ comments/questions, recorded the number of people participating in community outreach and documented audience testimonies and feedback.

Because the consultants were not fluent in some of the campaign languages, CCP hired transcribers who listened to recordings of call-in programs in those local languages and prepared verbatim English transcripts, which the consultants reviewed. Every month, the consultants prepared monitoring reports, which CCP compiled and shared with the advertising agency to improve future programming.

- Community Outreach Broadcast Guide for Bilharzia Campaign, Uganda

- Uganda Schistosomiasis Prevention Communication Campaign – Radio Monitoring Plan

- Schistosomiasis Prevention Communication Campaign Plan

- Agenda for Radio Broadcasters Meeting – Bilharzia Campaign, Uganda

Evaluate and Evolve

CCP used both quantitative and qualitative methods to evaluate the campaign.

Qualitatively, CCP interviewed select people who participated in community outreach radio programs to document stories of how the campaign affected them. Quantitatively, PMA2020 incorporated questions into its 2017 Schistosomiasis Survey about exposure to campaign media, recall of campaign messages, and measures of self-efficacy. The 2017 survey fieldwork took place during October and November, two to three months after the campaign launched in mid-August.

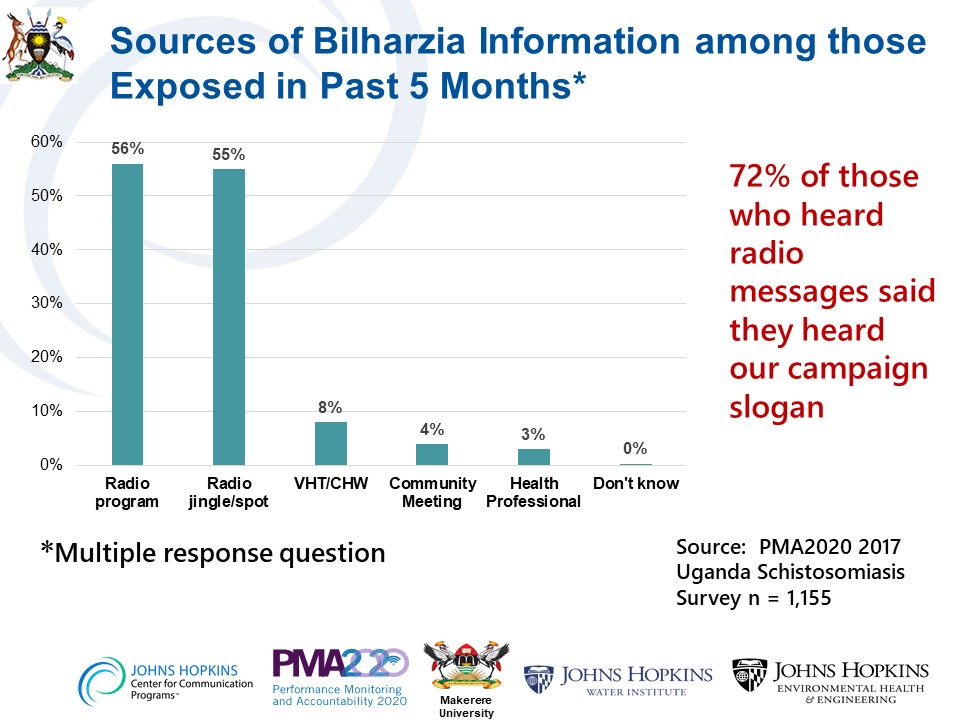

After only two to three months on air, the campaign had reached more than half the population of Uganda, most of whom resided in Bilharzia endemic communities. According to the 2017 PMA2020 survey, 66% of Ugandans had heard a radio message about Bilharzia in the five months prior to the survey. Some 72% of them had heard the campaign slogan “put a stop to Bilharzia before Bilharzia stops you.” By far, the greatest source of Bilharzia information over the five months prior to the survey were the radio spots, jingle, and programs.

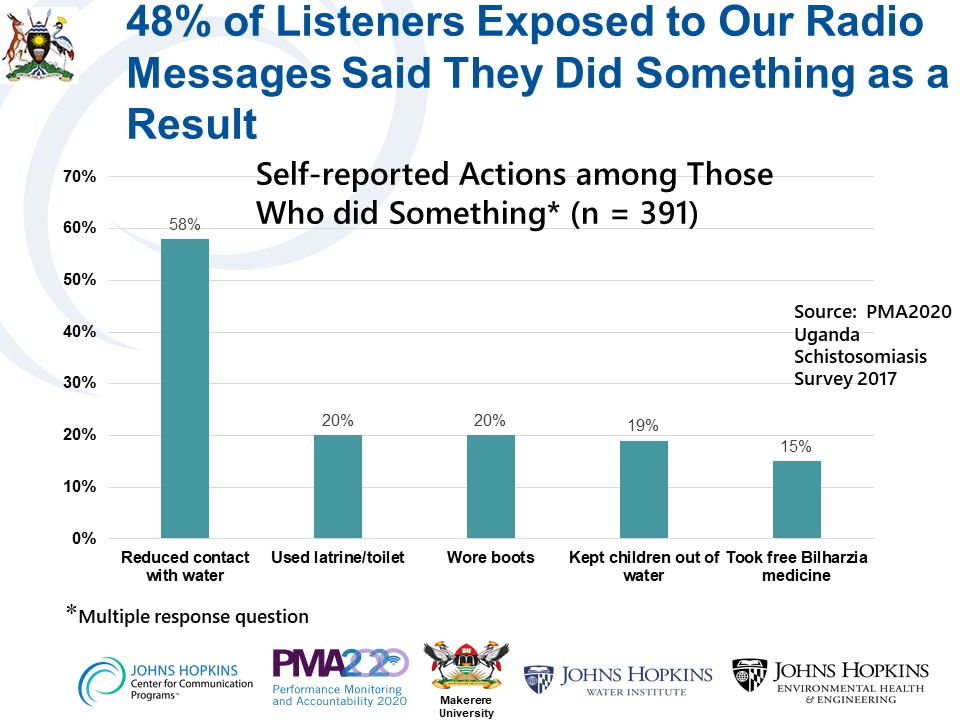

Almost one half (48%) of respondents who were exposed to campaign radio programming said they had taken some action as a result. The most common action, reported by 58% of those who reportedly took action, was to reduce contact with fresh water bodies.

CCP collected many stories from people who benefited from the campaign. One of the most moving testimonies came from a man living in Bugiri District, which borders Lake Victoria:

“A relative of mine got an illness which caused his stomach to swell and many people thought that he was bewitched. We took him to different witch doctors but the last one we visited asked for 400,000 Uganda Shillings (approximately US $100). He put us in a shrine, locked us there and made us chant songs to evoke spirits. He later asked for a goat which he slaughtered and asked us to leave without looking back. In August, while listening to radio, I heard a guest expert talking about Bilharzia and I asked my relatives to take the patient to Bugiri main hospital to see if he was suffering from Bilharzia.

There it was confirmed that he had Bilharzia and he was treated. As I speak now, he is better and has a lot of appetite. Thank you.”

The campaign also inspired people to become champions for Bilharzia prevention, sharing the message on their own steam.

One such man is Muhumuza Eliphaz of Kamwenge

One such man is Muhumuza Eliphaz of Kamwenge District, a highly endemic district that borders Lake George. He lost a neighbor to Bilharzia a few years ago, when most people had never heard of the disease. Since the campaign began, two of his other friends got treatment and have recovered. He credits the campaign with saving their lives, and has composed a song in his local language about Bilharzia, which he performs in the villages near his home to share information about the disease and how to prevent it.

- Schistosomiasis Monitoring in Uganda, Round 2 October–December 2017

- A Media Campaign to Prevent Bilharzia in Uganda

Date of Publication: April 20, 2022